Warning: Undefined array key "options" in /var/www/wp-content/plugins/trx_addons/components/api/elementor/elementor.php on line 1687

WHY REPRESENTATIVE FAISON IS SO PASSIONATE ABOUT ORGAN DONATION

After a bad car crash in 1989, Faison’s parents declined to take his sister off life support to donate her organs — and Faison has struggled with that choice since

Brad Schmitt

Nashville Tennessean

• * Becky Faison died at 16 years old, leaving her younger brother devastated

• * Hospital doctors begged Faison’s parents to let them recover her organs to save other lives

• * Faison’s parents, in shock, felt like the doctors tried to strong-arm them, which made them angry

More than 30 years later, Jeremy Faison still regrets doing it.

At 13, he snuck into his sister’s ICU hospital room a day after she got into a bad car wreck.

Her eyes bulged out of her swollen head, and a tube stuck out her mouth as a machine breathed for her.

“The way her eyes were, it was like someone put a baseball in each eye socket and covered it in blue,” he said. “It was traumatic for me. I was devastated.”

This was his sister Becky, the only one of his three siblings — all older — who gave him the time of day.

The only one who hung out in his treehouse with him.

The only one who hugged and kissed him goodnight, every night.

He had to see her, even though his parents and hospital staff forbade it, even though it broke his heart.

Because Faison had to tell her something.

“Please, Becky, please wake up. We need ya’,” he said. “Please wake up.”

She never did.

Rebecca “Becky” Eleanor Faison, only 16, died April 20, 1989, five days after getting in a car crash with her sister while the two were picking up kids for vacation Bible school at their daddy’s church. The other sister, Cara, survived.

A drunk driver hit their car, leaving Becky Faison brain dead and sparking a tense stand off between her parents and hospital doctors who wanted to take her organs for other patients who needed them to survive.

The girl’s parents refused, hoping their little girl would pull through, clinging to the advice of a physician in their church congregation who told them to wait at least 72 hours before taking her off life support.

Faison’s mother, Romesa, still thinks they made the right decision. She still resents what she says was the heavy handed approach from hospital doctors.

But Faison is convinced his sister Becky would’ve wanted to donate her organs. Because Becky always wanted to help others.

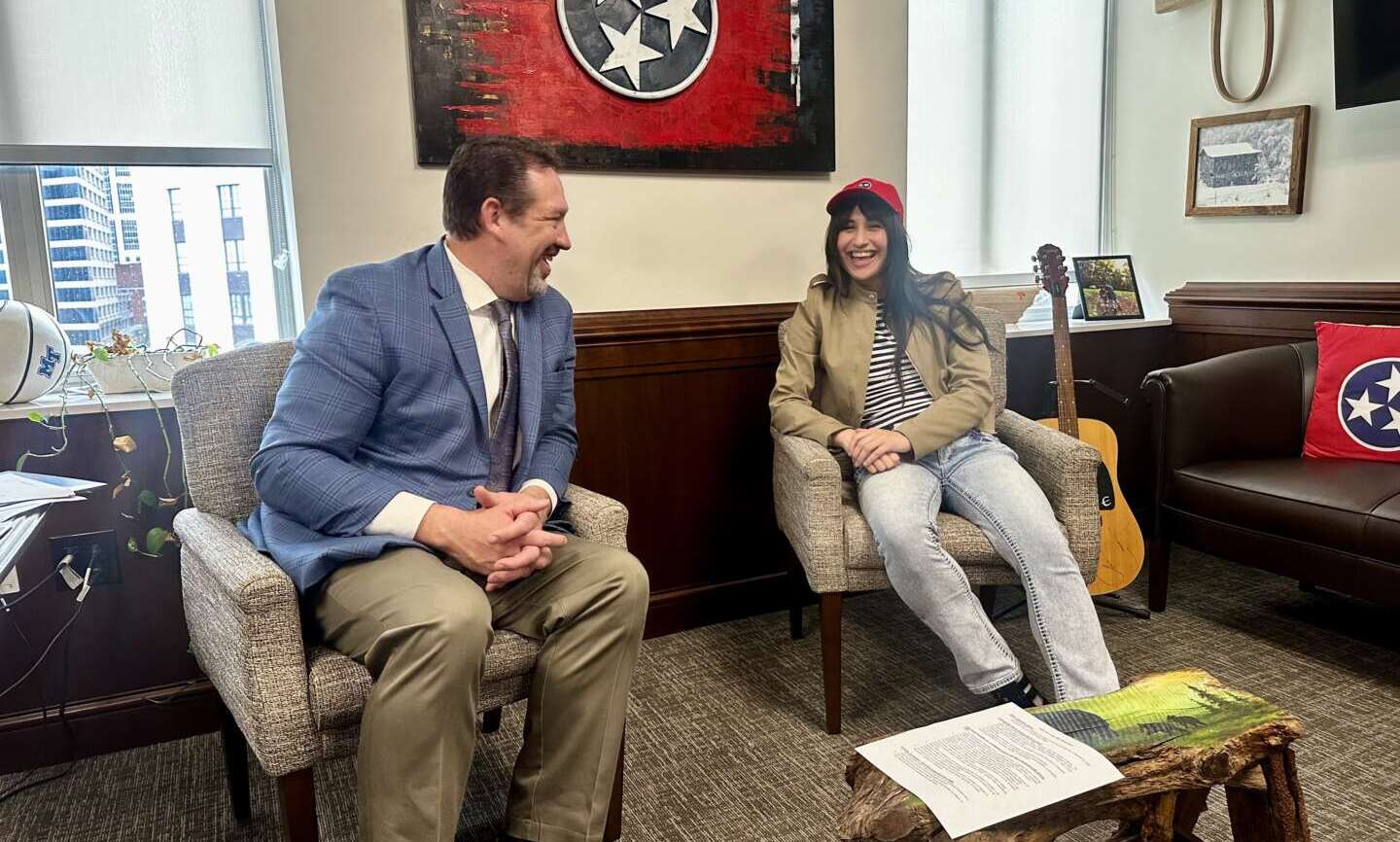

Now the House Majority Caucus Chairman for the state legislature, Faison is encouraging Tennesseans to sign up to be organ donors.

He’s doing so to honor his sister’s memory — and to empower others to make a choice Becky Faison never could.

‘We gotta go’

The youngest of four kids, Faison said he constantly was into something, buzzing around and bugging his siblings.

His older brother and sister pretty much blew him off. But not Becky.

She was the only one to climb into the treehouse he built behind the family’s ranch home in tiny Higginsville, Mo.

She even rode the zipline he built coming out of the treehouse and ending at another tree.

It wasn’t a safe ride.

“You had to land it running,” Faison said, smiling. “We put a huge mattress on the tree in case you went too far,” which many did.

Brother and sister often rode scooters together and got cherry Cokes from the local drug store, where Becky taught him to tie cherry stems into a knot inside his mouth.

Faison wasn’t the only one to benefit from Becky’s kind, inclusive and adventurous spirit.

At Faith Baptist Church — where their daddy was the preacher — daycare volunteers often fetched Becky to soothe crying children.

“She was a very loving child,” her mother told the Tennessean. “Everybody in the family had a special relationship with her.”

The day of the accident, Faison was playing with a friend when they heard emergency vehicle sirens. The two joked about the law coming to get them.

About 20 minutes later, Faison’s father charged out of the house yelling.

“Jeremy, we gotta go! Your sisters have been in a wreck.”

They soon found out that older sister Cara would be OK, but that Becky needed to go to a trauma hospital in Kansas City about an hour away.

The doctors were bleak: She’s got severe head trauma. She’s on life support. She’s brain dead. She’s not going to make it.

Hours later, the doctors asked the parents about taking Becky off life support to have her organs donated. The parents dug in, saying they would follow the congregant physician’s suggestion for waiting 72 hours, way past the point the organs could be viable for others.

The physicians asked several more times, and the upset parents got angrier and angrier.

“My dad just bowed up on them,” Faison said. “My dad was ripped.”

Faisons’ mother said it was hard to think about donating organs while realizing they were losing their daughter.

“It’s such a horrible shock to think your 16-year-old daughter is dead. It’s just unbelievable,” she said.

“They just really put the pressure on us. That ticked me off. You’re a mom, so obviously you don’t want to let go no matter what.”

The right thing to do

Faison, even at 13, saw things differently.

“I remember thinking, why can’t she give her organs and save other people?”

Grieving came hard for Jeremy Faison.

“There were nights I’d wake up torn up, crying my eyes out. I remember hurting so bad that I didn’t know if I could breathe,” he said. “I was crying to hard, it took my breath away.”

Gut punches came when a favorite Becky song would come on the radio, especially Stevie Wonder’s “I Just Called To Say I Love You.”

A lifelong believer, Faison said he questioned God.

“I told God at one point, if you are real, I don’t like you, because a loving God wouldn’t let me hurt this bad.”

The issue of organ donation came up three years later when Faison got his driver’s license and his father wouldn’t let him check the organ donor box.

“No, they’ll want to take ‘em while you’re still alive,” said his father, who died in 2012.

When he was about 24, though, Faison checked the organ donor box when he got his license renewed.

“Because of my Christian faith, I am pro life, and outside of adopting a child, I don’t know if you can be more pro-life than if you give your organs to someone who needs them,” he said.

“It’s always been in the back of my mind — man, If we could’ve saved some lives by donating Becky’s organs.”

The issue came up again in February when Faison was teaching at his daughter’s school in East Tennessee, and a student did her senior thesis on organ donation. It made Faison want to be more proactive as a legislator.

He shepherded a resolution through the legislature urging Tennesseans to participate. The resolution passed unanimously, but, he added, “I found it’s a little taboo. There are some people who struggle with it.”

One of them is his mom.

“I’ve never really been against it. Except the thought that came to me, I have to give up a life in order to save a life. And is it mine to give up?” she said.

“We spent a lot of time wondering if there was life in that body. Given all the cards I was dealt, I don’t know that I could’ve done anything different. I did the very best I could do. I don’t feel I made a big mistake.”

In addition to the resolution, Faison is working with Tennessee Donor Services on a campaign — #BeTheGift Tennessee! — to get 100,000 more Tennesseans to register as organ donors before year’s end.

“This is the right thing to do. I’m 100 percent sure Becky would’ve donated her organs,” Faison said.

Faison also is in a better place with God.

“There have been so many awesome things that have happened because of my sister’s life and her death, I wouldn’t change it. I can see the hand of God through all that,” he said.

“It took several years to get there. But I’m there now.”

Reach Brad Schmitt at brad@tennessean.com or 615-259-8384 or on Twitter @bradschmitt.